A few months ago, Russ Taylor and I wrote an Op-Ed on the opportunities that Big Data presents in Africa. This article focused on our findings within the South African context, and I wrote about my experience with the African Research Cloud Astronomy Demonstrator ProjEct, ARCADE.

The teaching and learning intervention didn’t really start off as a specific case-study for big data, or data intensive computing, or cloud computing. Indeed, the project didn’t even start off as an intervention, since I was aiming to solve a simple problem – teaching my class of 50 students how to do a straightforward statistical analysis on radio and optical images.

The students were from a variety of different social and academic backgrounds. The engineers had experience to digital signal processing, while the scientists had just started learning about Fourier Series. Some of our students had their own laptops and plenty of experience with computers; others were only just developing their expertise in computing. Throw into the mix the vagaries of installing astronomical software. Thus, the challenge was to provide the students with comprehensive, persistent access to software tools and data required for the project.

There were three options available:

- Have the students install the software on their own computers.

- This was a non-starter, since it would’ve taken longer for us to troubleshoot installation problems than the time we had available.

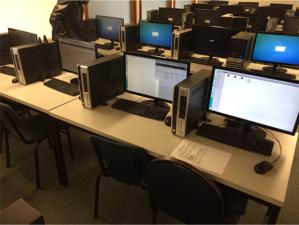

- Use the SCILAB Computer Labs at UCT.

- While we could easily accommodation the 50 students, we would not be able to provide persistent access to the data. Plus, most of the radio astronomical software is primarily available for Linux-based installations, which would’ve been a problem for the Window’s based systems in the SCILABS.

- Use the NASSP Labs at UCT.

- This lab comprised about 25 computers running off a single server, so we could only

accommodate a single group at a time. We were able to install the required software and

provide access to the data, the sheer load of having 25 students logging in at the same

time crashed the sytem.

- This lab comprised about 25 computers running off a single server, so we could only

accommodate a single group at a time. We were able to install the required software and

provide access to the data, the sheer load of having 25 students logging in at the same

time crashed the sytem.

Each one of these options were unfeasible, but a 4th option appeared. Why not use the SCILAB’s and the students’ own computers (or mobile devices) as thin clients for another, larger server?

It took me a while to connect the dots. I had been working on ARCADE for a few weeks, setting up smaller virtual machines on the cloud for tests involving astronomical computing for IDIA. The typical use-case involved providing access to a large number of researchers to a comprehensive computing environment. There was thus a clear correspondence between the astronomical computing use-case, and the training use-case. Indeed, the training use-case was a little more involved, since we were getting about 50 users to login and hammer the system simultaneously.

So we spun-up a large, single-purpose Virtual Machine, which used the Jupyter-Hub as the primary interface. We then created accounts for each student, dumped a copy of the data and an example notebook into each user-account’s home directory, and presented the Jupyter-Hub via a web-server. Each student was able to login to the system using the web address – https://arcade-jupyter-hub.uct.ac.za.

This was an enormous success. Each student worked at their own pace, and their access to the

machines were not limited to a single computer; they could access their dashboard anywhere on

campus; access was limited to the UCT campus, but access can easily be extended to the world.

There were a few interesting lessons that we learned along the way. In our Op-ed I outlined how a well designed cloud is like “IT-on-a-diet”, and is an ideal approach for South African companies and organizations that don’t necessarily have the benefits of large IT budgets. However, it does rely on some proficient and sharp expertise being available. AWS users, for example, would leverage AWS tech support, and you can easily appreciate that supporting and administering cloud-based services is distinctly different from sys-admin’ing a local server. So while your requirements have shrinked, they haven’t necessarily simplified, and I relied heavily on the dedicated, real-time support from a single technical specialist to help setup and manage the machine.

The complex issue of setting up and exploiting the flexibility of the cloud was soon tested with our ARCADE/Jupyter-Hub VM. While I had done a generous back-of-the envelope calculation of the system requirements for the class of 50, I soon realised that it was difficult to ensure efficient resource usage by such a large group. Buffering the radio and optical images began to eat away at our RAM allocation, causing the usual cascade effect – simple Python tasks were crashing, and I/O was choked down to a crawl.

This was solved after the fact; we scaled the RAM allocation by hand while the machine was still up – which is exactly one of the main use-cases of the cloud. In practice, if we had been smarter, we would’ve used a Docker Swarm or some other form of back-end scaling equivalent to elastically scale the resources of the VM, without having to worry about doing this by hand.

In the end, the exercise was an enormous success, and paved the way for our modus-operandi at IDIA. At IDIA we provide access to our large VMs via the Jupyter-Hub and also via SSH, but we rely on Singularity containers instead of Docker, simply because of security considerations. We showed how large VMs can be spun up, made accessible to a large number of users, and how the resources can be scaled to take into account the changing needs of the user-base. I am still using the ARCADE/Jupyter-Hub VM for the second-year class, and I’m confident that we will be able to extend our expertise so that we can develop an easily deployable solution for many long-tail use-cases.